Meal-prep Automation

My own struggles with eating well and cooking respectable meals combined with my need to break my teeth on process capture has resulted in this project. Cooking recipes are a relatively low bar in terms of capture and codification as they are short, contain a table of nouns (ingredients) and have limited context while trying to apply NLP. The lessons learned from this project will help define the general problem of Knowledge Capture.

Note: This is a live document and will be expanded upon as this project progresses

Tea, Earl Grey, Hot

Those words are famous, and said right before a cup of hot tea was automatically prepared. While we are a long ways off

from converting energy directly into complex matter in a household appliance, we can begin to address some of the problems

that the replicator from Star Trek solved.

Those words are famous, and said right before a cup of hot tea was automatically prepared. While we are a long ways off

from converting energy directly into complex matter in a household appliance, we can begin to address some of the problems

that the replicator from Star Trek solved.

While taking business classes, my institution required us to identify pain points in the community and prototype businesses to try to serve them. There was a strange recurrence of the same issues every semester that different groups kept identifying. Three of them were food waste, food delivery, and good nutrition. Food waste is a troublesome problem because when you go to assess the volume of food wasted by industry each week it is collectively enormous relative to an individuals’ perspective but relatively small compared to the size of the industry. The reason no one has ever found an effective solution was because it nearly always boiled down to a logistics problem.

Students, busy professionals, and households requiring dual incomes have ever decreasing available time for tasks like grocery shopping and preparing meals. The growing markets for grocery and restaurant delivery are the evidence of this. People want to eat healthy but don’t have the time to pursue elaborate meals and will opt for ‘fast food’ or prepackaged meals. The effectiveness of these solutions all boil down to how well they can address the ever pervasive last mile problem. The cost of a product is largely determined by the number of hands that need to come into contact with it before it arrives at the consumer.

So the question becomes: What is a solution that maximises food quality, variety, and freshness while minimising food spoilage, cost, and human involvement before it can be consumed?

Like most problems, the answer generally involves automation. To maximise food freshness you need to minimise processing of the food up until just before it is consumed. This means that you need to capture as much food preparation processes as possible in a machine located as close to the consumer as possible. The alternative to this is exploring preservation processes, allowing more factory processing long before products get to the customer. Food preservation has proven to significantly reduce the nutritional value of food while also introducing chemical products that would not otherwise be present.

Problem - Human = Harder problem

It is often frustrating to see engineers approach an automation problem by simply trying to replace the human in the

process. The end result is usually a poor approximation of a human, with a very narrow range of functionality, designed

to replace the manipulation of the tools that were originally designed for a human. Trying to engineer a replacement human

is a massive task to get right, and while advances in robotics and artificial intelligence are making it more viable, it

is unnecessary and solves the wrong problem.

It is often frustrating to see engineers approach an automation problem by simply trying to replace the human in the

process. The end result is usually a poor approximation of a human, with a very narrow range of functionality, designed

to replace the manipulation of the tools that were originally designed for a human. Trying to engineer a replacement human

is a massive task to get right, and while advances in robotics and artificial intelligence are making it more viable, it

is unnecessary and solves the wrong problem.

The other side of this is found in industrial automation. Brilliantly engineered machines and processing techniques that do a single task very effectively, at scale. These solutions are effective because the engineers are handed a very well-defined problem with strict constraints on the operating environment and input materials. In order to find an equally effective general solution to food preparation, the problem needs to be equally well-defined. This means capturing and understanding the whole problem, and all of its inputs and outputs.

The secret to finding the right solution is by solving the right problem

Capturing the whole (and correct) problem involves cataloging every possible food recipe, and food product that we intend to automate preparing. Conceivably you could just go one by one and build a machine that produces one recipe each, but that is infeasible, and the end product would be enormously complex. The problem then needs to be reduced by finding commonalities between all the processes and try to find reusable mechanisms to address as many as possible without compromising quality of product.

For example, consider recipes describing the processes of mixing, blending, stirring, folding, kneading, whipping, (and many more verbs that I am sure are exclusive to cooking). They are all effectively trying to homogenize a mixture of substances. They are not necessarily immediately interchangeable though, especially within the context of a recipe. This is where capture of the recipes and ingredients alone are not enough to successfully reproduce a recipe. Knowledge capture of cooking professionals needs to occur, and that knowledge needs to be refined.

Molecular gastronomy is the field of study that seeks to better define culinary processes in terms of chemistry. The work from this field can be used to further narrow the problems we are trying to solve with automation. Once we understand the underlying principals of what a machine actually needs to accomplish we can begin to design it. Returning to the mixing example, if the goal is simply to produce a homogenous mixture, you could use a conventional means of doing so. This would involve dropping the materials in some sort of container, inserting some equivalent of a spatula, and agitate the contents until it seeks a level of disorder via entropy. This approach depends on a random process, and it would be difficult to control it in a way that would serve all the variations required by all the recipes. This would be too close to trying to replace the human.

Machines are much better than humans at doing meticulous work quickly. This can be leveraged to produce a homogenous mixture by placing each finite granule exactly where it needs to be. Imagine something like a 3D printer, placing each ingredient, layer by layer, in the exact pattern desired for the mixture. This approach would allow infinite variability of the mixtures and more readily serve the wide variety of needs of each recipe. The only limitation would be the machines’ ability to manipulate each ingredients’ granule in the mixture at the scale required.

The second solution seems like it would be a better option, but it needs to be restated that that can’t be known until the problem is actually captured. It is very likely that a combination of the two methods, or even a third method would be more appropriate. The point is that the problem needs to be fully defined first, and only then can unconventional approaches be effectively hypothesised.

Finding the right problem is a problem

Given the ambitious scale of this project, it demands some level of automation to just define the problem. Currently, all recipes are stored in loosely structured natural language (English, French, etc.). Many of which are not even encoded as text in a computer readable format (Books and images). Technologies need to be leveraged to automate much of the task of codifying and restructuring the information in a format that allows computers to manipulate the data en masse. This means pulling in Natural Language Processing, Optical Character Recognition, and a variety of data transformation, storage, and visualization systems.

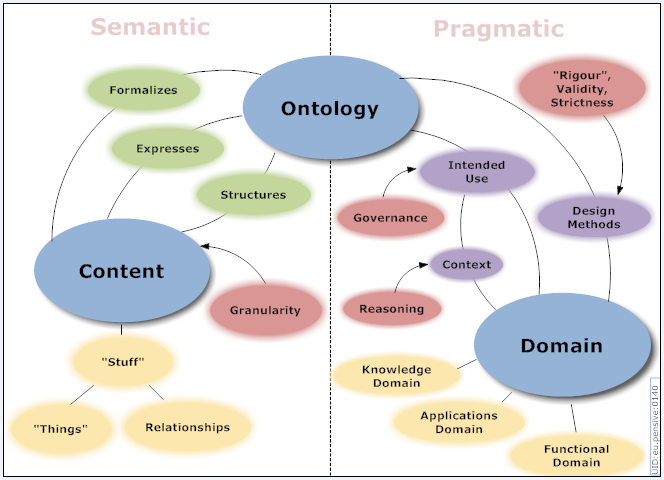

Similarly, for knowledge capture to occur ontologies will

need to be used if not created. Luckily existing projects have

already started this work. It is important to leverage as much existing work as possible, greater success can be found

by standing on the backs of giants. An ontology will give a structure for defining the processes in terms of the

underlying concepts, materials, their properties, and all the variations thereof. Collection of the processes into a

graph structure will allow the application of graph theory

/first order logic to help reduce the problem.

Recipe complexity

The plan is to collect recipes from both books and websites, each source providing its own challenges. Books require capturing text from images, while also retaining the location of the text within the image. The spacial information of the text allows making decisions on the relationships and meaning of the information. This is especially important when trying to extract tabular data which an OCR solution may not be aware of. This also provides the opportunity of predefining document layout patterns that would allow the automatic exclusion of extraneous text.

Websites pose a more varied challenge in that some sites take measures to protect their recipes from being automatically scraped. Recipes can be rendered by the browser or pre-rendered and transmitted as an image. It could potentially be easier to convert websites to images and process them through the same pipelines developed for books. Only retaining HTML data for the purpose of providing hints to the OCR and data cleaning stages.

At each stage of the collection process, data that is collected from different sources should need to be prioritised. Aiming to capture 100% of the available recipes will likely have diminishing returns. The target should never be 100% capture or 100% automation. If effort is made to gather as many recipes as possible at the outset then the data capture pipeline will only exist to process that data. New or undiscovered recipes that are deemed important can always be manually captured afterwards. The initial database can also be used to inform more effective capture methods in the future.

Ingredients

Before NLP is applied, the capture problem needs to be further simplified by identifying and isolating the ingredients and directions. The ingredients will mostly be presented as structured text, either a table or list, requiring a different set of heuristics. Quantity, unit, name, brand, annotations, and alternatives are potentially present for each ingredient line. The first two can likely be captured with a simple regular expression while a collection of heuristics will likely be needed to capture the semi structured remaining fields.

Directions

Interpreting the directions is where NLP techniques will likely be most potent, but not before employing some heuristics to differentiate paragraph form vs list form. Even then, NLP won’t immediately solve the task of determining the temporal relationship of tasks. Recipes rarely have an entirely serialized series of steps, there are tasks that should be described as asynchronous. A dependency chain of events described in the recipe directions needs to be eluded from the noun-verb information along with the textual ordering. Directions will also list criteria for the progression of the steps, sometimes described explicitly, sometimes described with a simple adjective. An ad hoc approach should generally be followed, refined until an acceptable number of recipes have been captured at an acceptable level of ambiguity.

Good enough

Even if the goal was to capture 100% of the recipes, a measure of the fidelity of the generated database will need to be established and automated. Validation is potentially a more time-consuming task than capture and needs to be automated.

Methods to do this can include:

- aberration detection of ingredients and their quantities between similar recipes or globally

- establishing ingredients with rational proportions to other ingredients independent of any recipe

- simple time and temperature thresholds

- outlier detection via clustering of processes and ingredients

- correlation of interdependent quantities extracted with a recipe (total prep time vs. sum of times of steps, mass of ingredients vs predicted mass of products)

- comparison to a manually curated subset of recipes, selected to maximize commonalities with the full dataset

The goal of these measures would be to flag captured recipes for manual review. The ingestion process can be iteratively refined based on these measures until a satisfactory level is reached, possibly truncating the dataset at a desired threshold.

Additional sources

The recipes themselves only describe what to do with the ingredients. Additional information about the variations of ingredients, significance, and tolerances also need to be established. The same goes for the processes, a recipe may describe a process (such as mixing, folding, chopping, searing), but the specific recipe requirements of that process, or what exactly the process is accomplishing, also needs to be specified.

Status

This project is currently waiting for time to be freed up from other ongoing projects.

TODO

- Collect as many cooking recipes as possible in any format available

- Evaluate unanticipated requirements for data ingestion and sanitization

- Preliminary data characterization and curation

- Secure funding for a molecular gastronomist and professional chef (same person?)